From Interface to Infrastructure

What occurs when fitness experiences evolve from app-based interfaces to spatial systems that coordinate space, time, and bodies beyond the screen?

Over the past decade, fitness apps haven’t just moved workouts onto our phones. They’ve changed how we relate to our own bodies. Instead of noticing when we’re tired, deciding when to rest, or building trust in our own judgment, we now look to streaks, timers, badges, and performance stats. Motivation comes from numbers and notifications, not from inner awareness.

At the same time, “third places” — the cafés, studios, and community spaces where people once gathered to connect and grow — have slowly shifted. Many now operate less as places for real belonging and more as carefully designed sales funnels, shaped by trends and marketing cycles rather than by the actual needs of the people inside them.

This case study looks at that shift through a fitness space where the app’s logic is built into the architecture itself. You make your choices before you walk in. Once you’re inside, the space takes over.

Instead of tapping a screen or scrolling through options, the design guides you — through doors and entry points, through scheduled timing, through the size and shape of the room, and through subtle signals in the environment that direct your behavior.

To understand this shift — from interface to infrastructure — is to see how control moves from the screen into the space itself. And once that happens, the real question becomes: what kind of independence, discipline, and freedom does this design actually create in the body?

When App UX Leaves the Screen

A spatial fitness system is a workout environment where the space itself directs your behavior. The building works like an interface.

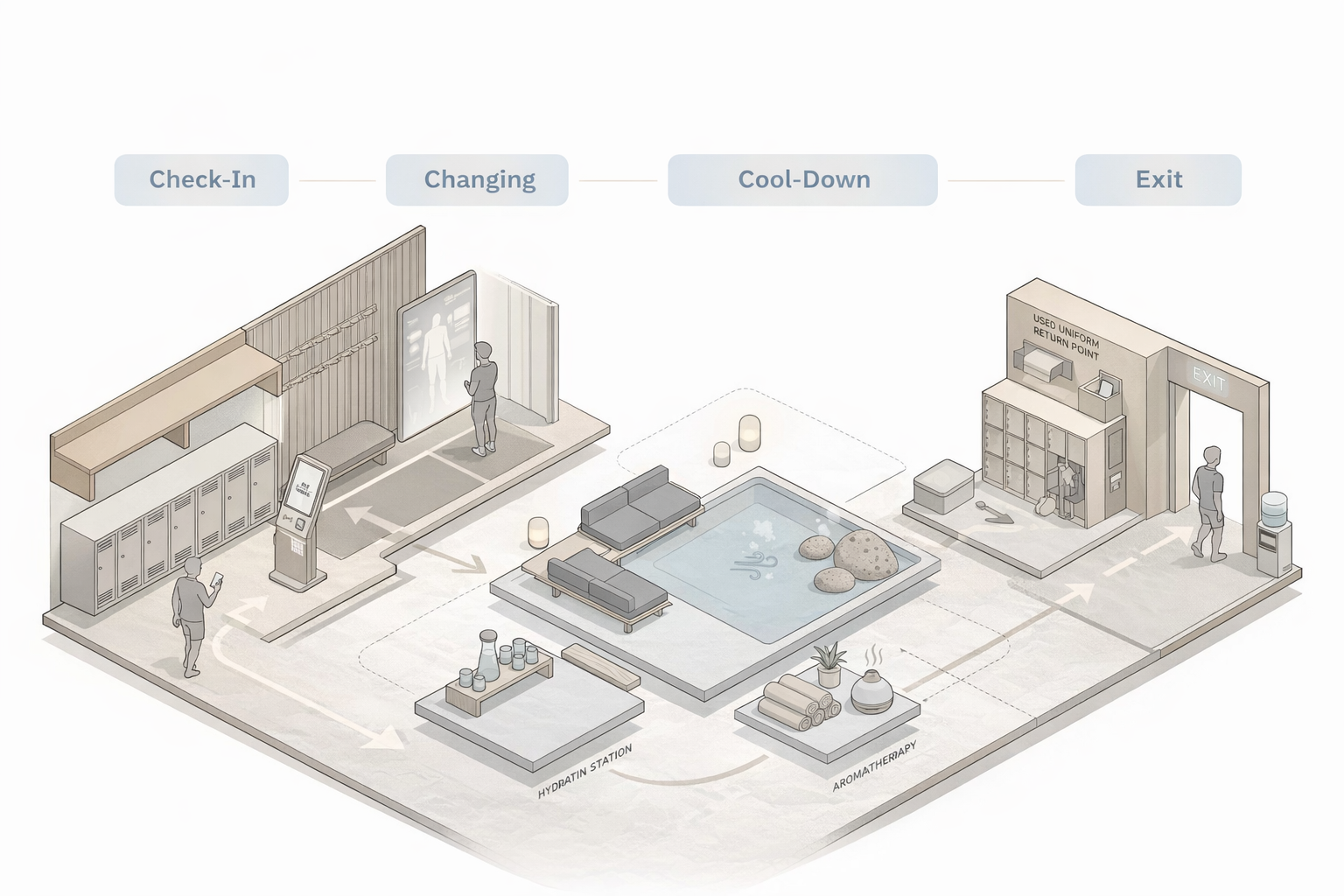

Instead of relying only on an app or a trainer, the room guides what you do, when you do it, and how long you do it. Layout, lighting, sound, timing, and equipment placement work together to structure the experience. The walls, walkways, machines, and enclosed rooms take over the role once played by signs and screens. You don’t read instructions. You move through them.

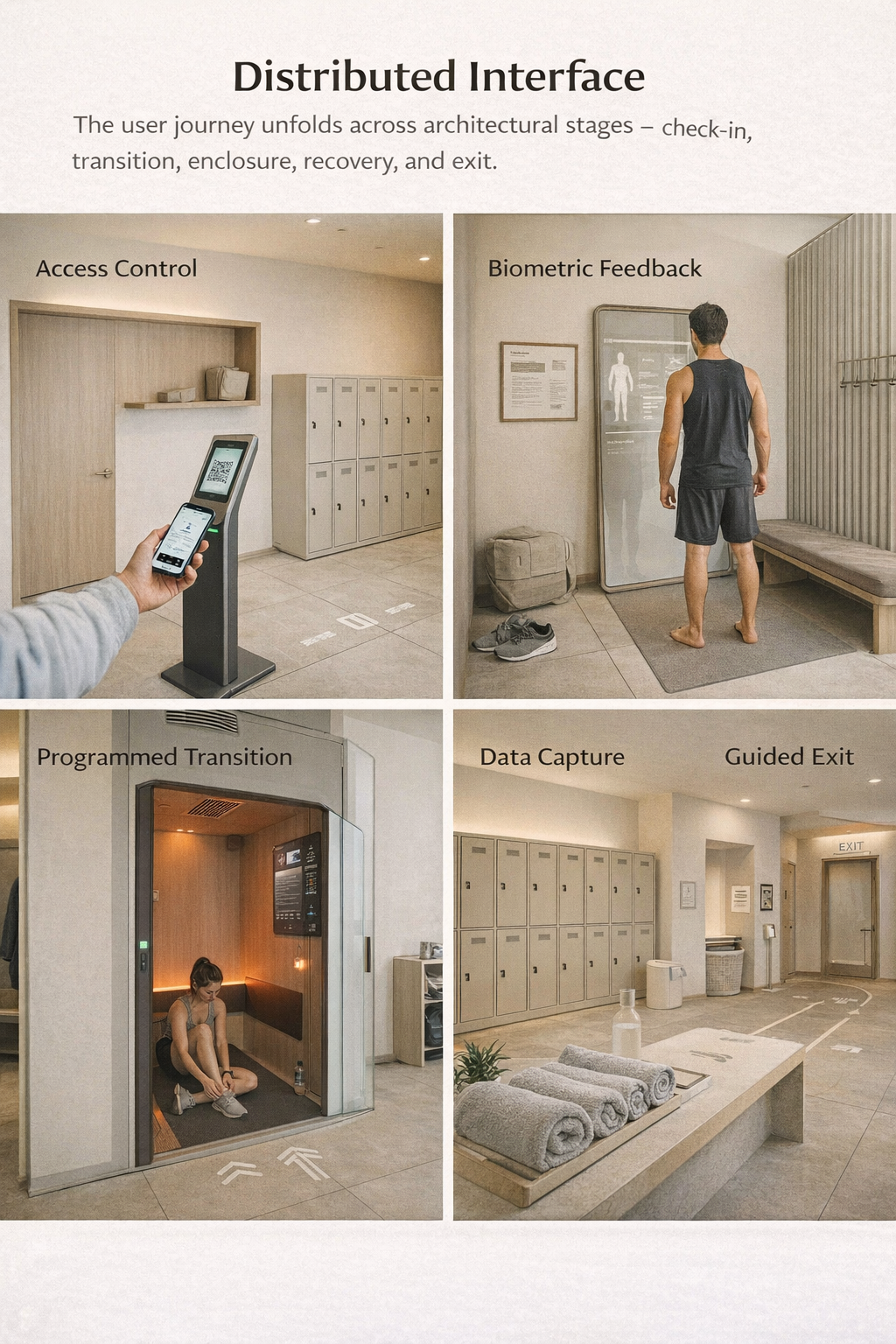

As these systems evolve into smart spaces, the phone changes roles. It is no longer just a display. It becomes a key and a scheduler. It unlocks doors, reserves time, verifies identity, and syncs your data across locations.

You may see fewer screens, but the system itself becomes more powerful.

When design moves off the phone and into the building, the problem changes. It is no longer about buttons or layouts. It is about how space shapes behavior. How it sets limits. How it creates routine. How it reduces choice in order to increase compliance.

The program defines the rules: who enters, how long they stay, what sequence they follow. Your membership profile refines the experience. The system tracks your history and adjusts access, timing, and intensity over time.

Control does not disappear when the phone leaves your hand. It relocates. It becomes architectural.

The Pod as Personal Trainer

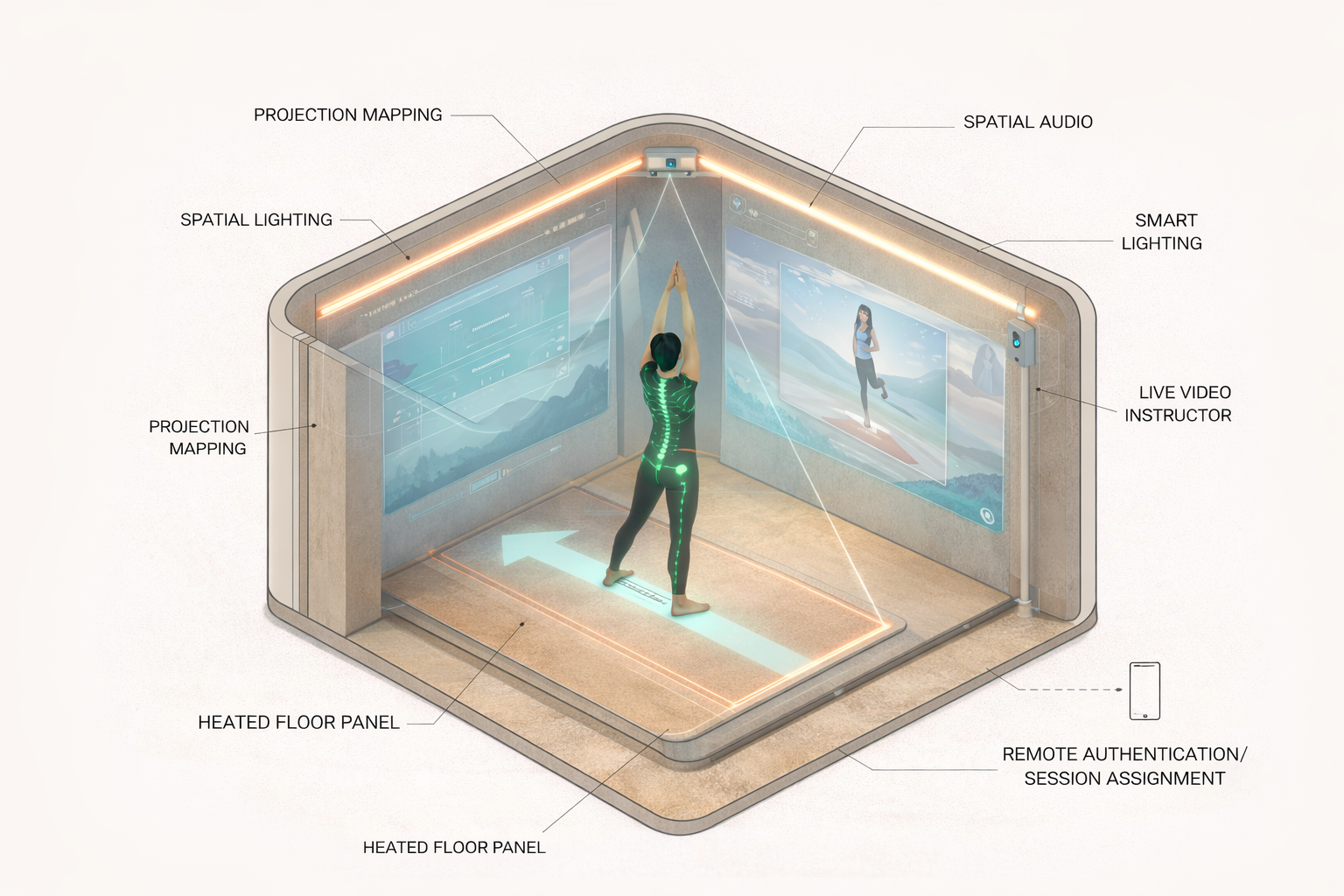

As fitness apps move beyond the phone, their logic does not disappear. It becomes physical. Timers, cues, feedback, and behavioral nudges move off the screen and into the room. Architecture stops being a backdrop. It becomes the interface.

The pod makes this shift clear. It does not simply host activity. It sets the conditions for it. Heat, light, sound, enclosure, and orientation take over the role once played by buttons, alerts, and progress bars. What used to be adjustable in software is now built into walls and thresholds.

This is not just a room. It is a controlled environment for the body. It isolates attention, standardizes the experience, and delivers a preset sequence of states. The phone still exists, but only as a remote control. It verifies access, assigns sessions, and tracks time. The main interaction now happens through space.

Framed as “somatic,” the pod promises focus and support. But it also limits flexibility. You can silence a notification. You cannot easily silence heat or step outside a tightly enclosed room mid-session without breaking the flow. When UX becomes environmental, negotiation becomes harder.

The diagrams that follow examine the pod not as a wellness object, but as architecture shaped by app logic. It is designed for repeatability, containment, and control. The key question is not whether spatial technology is good or bad, but what kinds of habits, behaviors, and forms of independence it creates in the body.

The UX Stack

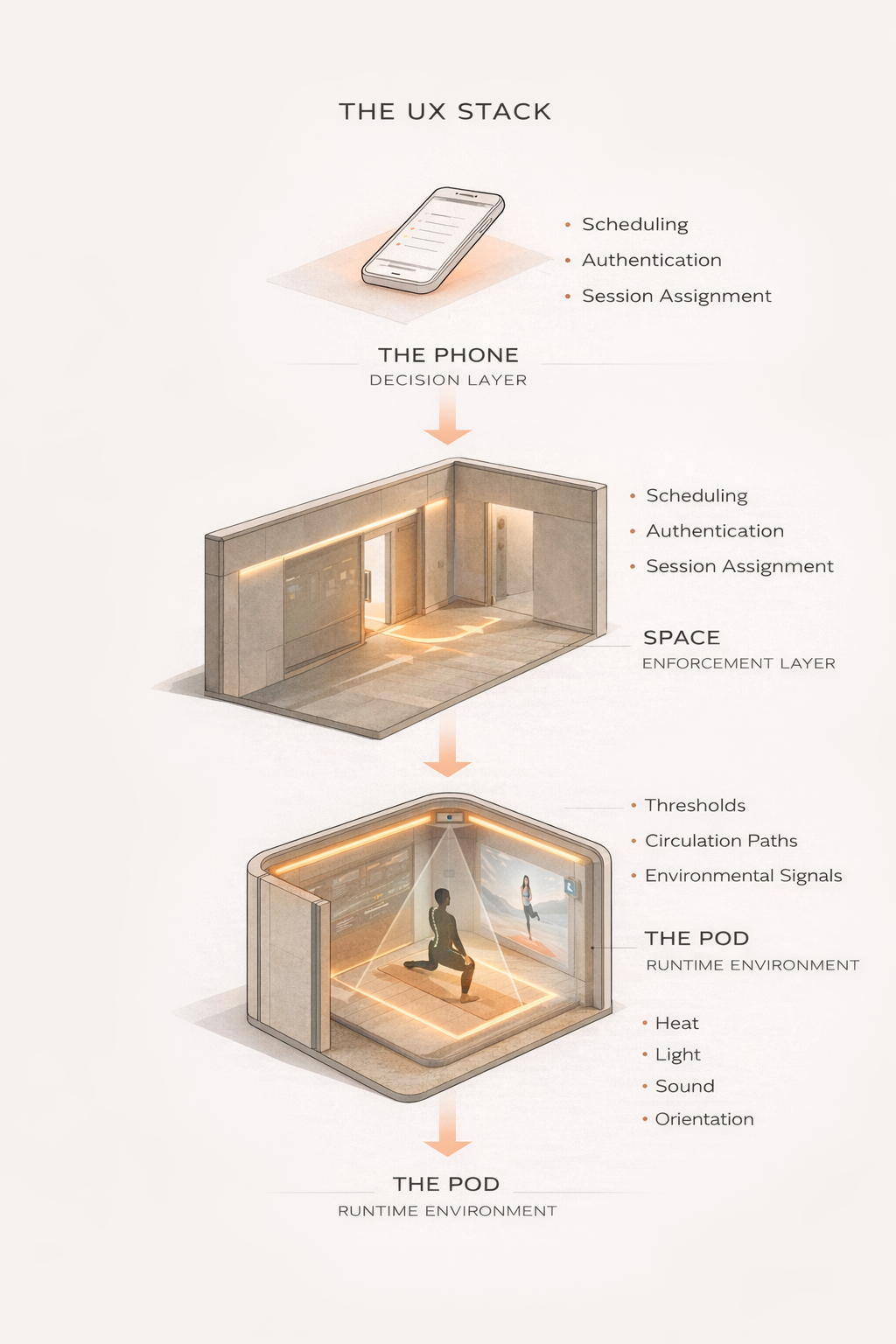

This system works as a layered stack. Control is divided across device, building, and enclosure. Each layer holds a different kind of authority.

1. The Phone — Decision Layer

Commitment happens here. You choose a time, confirm access, and agree to the conditions in advance. The phone stores your identity, history, and preferences. But once the session begins, it steps back. It coordinates entry. It does not manage execution.

2. The Space — Enforcement Layer

The building takes over. Doors unlock at specific times. Circulation paths guide movement. Lighting and sound signal transitions. The session has a beginning and an end built into the environment. These cues cannot be adjusted moment to moment. They structure behavior through thresholds, timing, and enclosure.

3. The Pod — Runtime Environment

Inside the pod, the logic becomes physical. Heat, light, sound, and spatial orientation deliver the session directly to the body. There are no visible menus and no ongoing negotiation. The experience runs according to preset parameters unless you leave the system entirely.

Together, these layers describe a shift. UX no longer lives primarily on a screen. It becomes distributed. Decisions are made upfront. Execution happens in space. Control moves from interaction to infrastructure.

Reading the System in Space

These diagrams do not describe a place. They describe a system.

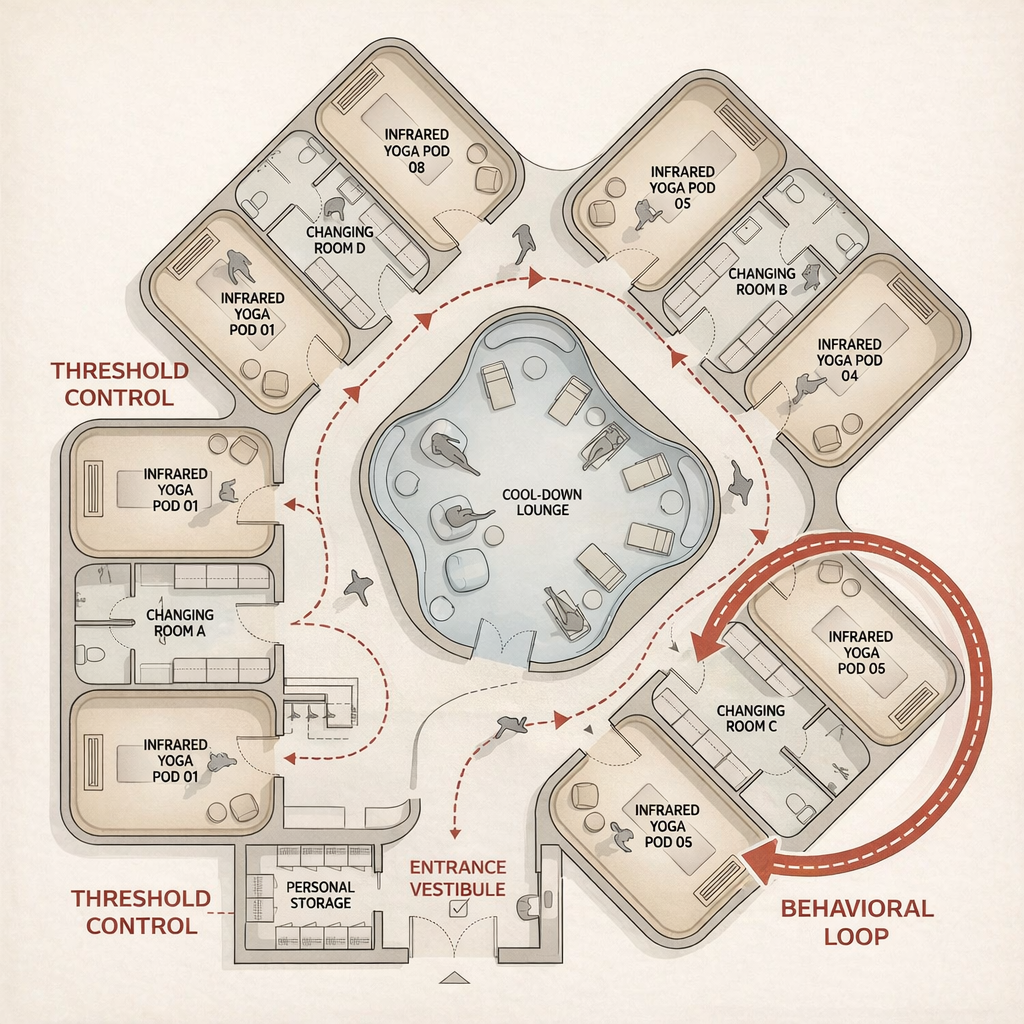

The user journey is procedural: entry, preparation, execution, recovery, exit. There are no branches. The body moves through a fixed sequence, like a task moving through an application flow. Architecture replaces screens, but the logic remains linear.

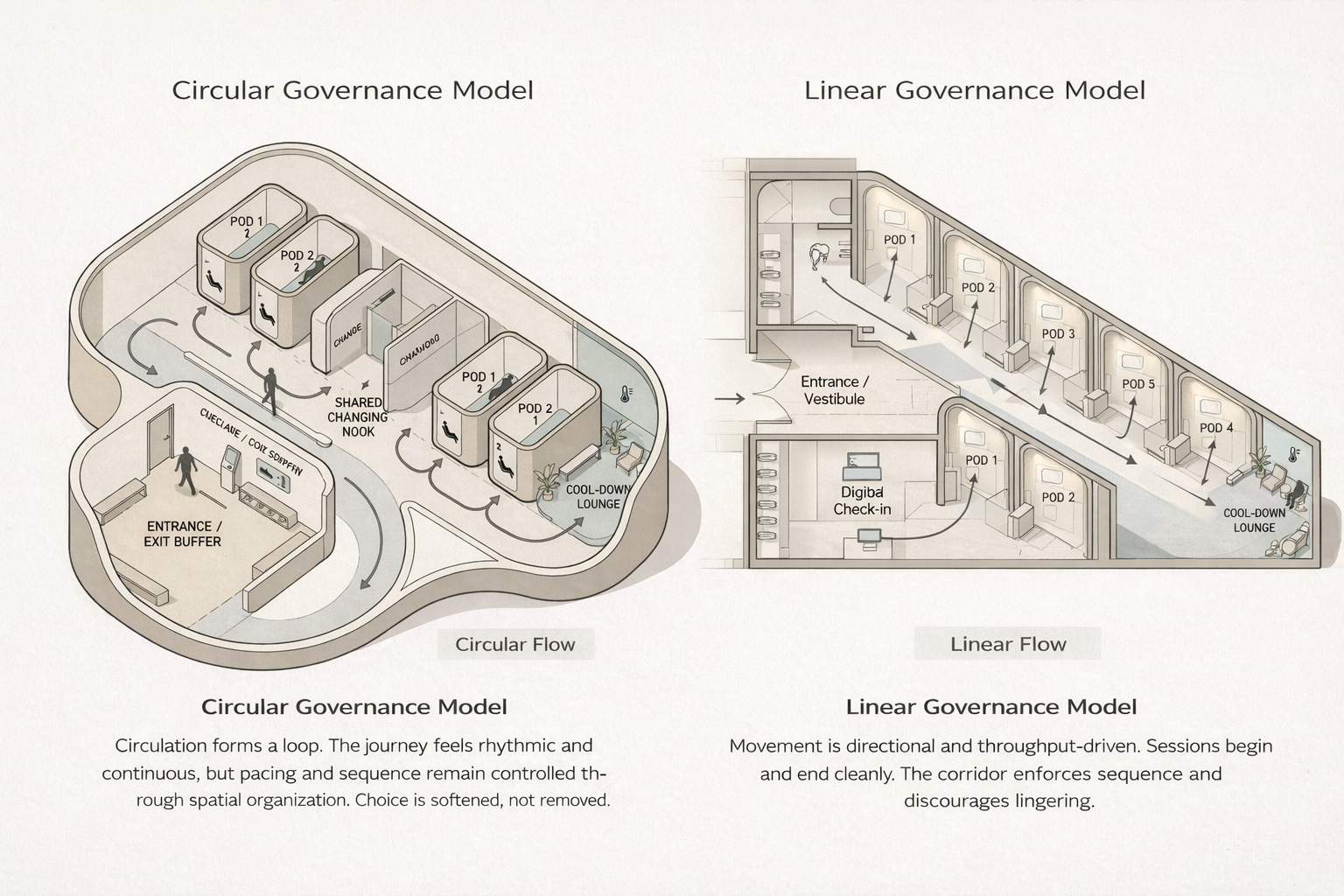

The layout comparisons reveal different styles of control. A linear plan prioritizes throughput and clean transitions. A circular plan softens the flow but still regulates pacing and duration. The difference is not freedom versus control, but how visibly control operates.

The pod is where the system resolves. Heat, light, sound, and enclosure execute the session directly on the body. There are no menus to adjust and no interface to renegotiate. Once inside, the experience runs as configured.

UX is no longer something the user interacts with. It is something the user moves through.

Why This Matters

When UX becomes spatial, agency changes. A screen can be ignored, paused, or closed. Architecture cannot. Once app logic is embedded into space, control operates through timing, enclosure, and movement rather than moment-to-moment choice.

This makes spatial technology inherently powerful. The environment no longer contains linear user journeys; it adapts and facilitates based on user behavior. As UX continues to migrate from interface to infrastructure, designers move beyond shaping interactions. They begin shaping the conditions under which autonomy is exercised. The question is not whether these systems function effectively. It is what kinds of habits, disciplines, and selves they quietly produce.

If the future of UX is architectural, then the future of agency is spatial.